Shipwrecks and Seascapes

NAS Report

This page offers a summary of our research from this semester. We conducted research in Mina Zayed and on the Bronze Age boat housed at NYU Abu Dhabi. This was adapted from our NAS report.

Introduction

The Arabian (or Persian) Gulf has long played an integral role within the broader Indian Ocean maritime world. The evidence of trade between Arabia and the broader Indian Ocean World extends back millennia, with shared maritime practices emerging throughout this time. One of the most evident remnants of these shared maritime practices is that of the dhow. While the actual term dhow has a contested origin, this term has become conflated with that of the familiar vessels that are seen throughout the Indian Ocean World. As such, this report will examine the history of Dhow culture within the UAE through a closer examination of a shipwreck in the Mina Zayed Shipyard and the experimental archaeology of the Bronze Age boat project.

This website follows the site location, determination, and surveying methods that we used within the Mina Zayed shipyard. It additionally explores the process of experimental archaeology at the NYU Abu Dhabi Bronze Age boat project. This research emerges within the context of the Shipwrecks and Seascapes course at NYU Abu Dhabi and follows a semester long class-wide research into local dhow culture. Each member of the class additionally pursued individual research with attempts to answer the question: What is dhow culture?

Site Selection

Choosing Our Research Sites

Mina Zayed

The first site we worked with was at Mina Zayed, Abu Dhabi's port. The site is easily accessible by car. In this area, there are several abandoned ships and shipwrecks, but we focused on one broken dhow with its larger rubble pile.

Even though the site is surrounded by steel fences, it is open to the public as the gate has always remained open during our investigation.

Our team conducted maritime archaeological research on the abandoned ships in the Mina Zayed Port. Even though the site is not underwater, we still consider it as a maritime archaeological site given that the site has a practical, visual, or structural relationship with a water body. The site represents the contemporary maritime landscape in the Gulf region. Given that we have found an abandoned ship, the site reflects how maritime culture is used to represent the local cultural identity in the tourism industry to attract more visitors. However, given that the site can be accessed by anyone, it is not protected. The site constantly changes due to anthropogenic activities and could hardly be preserved.

Bronze Age Boat

The second site was the Bronze Age site. It is located on Saadiyat Island in New York University Abu Dhabi on the east side of the campus. The site is an on-going experimental archeological project led by the university professors. It is easily accessible by students on campus. Even though the site is a modern construction, we consider the site a maritime archaeological site because the project provides insights to understand maritime practice and ship-building techniques in the Bronze Age. It asks important research questions such as: who built these boats? How were they built? How much manpower and time was required to build the boat? What did the boat perform? In that sense, the site provides us with a broader viewpoint about maritime history in the Indian Ocean. The site formation is an on-going process, as the project is to construct a boat that assembles the one of the Bronze Age. There are very few other factors that influence the site.

Site Location

Introduction

On day one of our field work our team traveled to Mina Zayed, the port of Abu Dhabi, to a shipyard where dhows and other wrecks are abandoned. Although we could see the shipwrecks in the yard, we conducted a circular search to reenact the practice of traditional underwater archaeologists.

Circular Search

A circular search consists of extending a measuring tape from an anchor, and then traveling in sections around a circular area. We started by extending the measuring tape to eight meters. We divided our group by 2 meters, meaning someone stood at the 2-meter mark, the 4-meter mark, the 6-meter mark, and finally the 8-meter mark. We then developed a communication system in case of a find or emergency to return to the top. One tug meant start, two tugs meant stop, and three tugs meant team members should come observe the found artifact.

Locational Bearings

To mark our circular search location and position, we took the GPS coordinates of our location. We also noted down locational bearings to find our position for the next day of field work because of their enhanced reliability. They ensure the ability to return to a specific site despite the lack of GPS. Our three bearings were the parking poles, electricity pole, and light pole.

Findings

On our dive we found three ships, which were then labeled and placed on a diagram. We selected one of these ships to research in detail, which will be explained later. Along the rest of our search we found various items including rope, textiles, wood, and glass.

Assessment

Mina Zayed is under Abu Dhabi government’s authority, but the city government does not have strict restrictions on who is permitted to enter. Therefore, the site is free for locals or us to conduct research. It is important to note, however, that if too much attention is drawn to the site, the government may restrict access to the ships (through destroying them, barring entry). Additionally, many locals/residents may leave behind garbage, thus contaminating the site. This causes complications in determining which items belong to the ships.

The site is above ground, and we were apprehensive about scattered debris like nails or broken glass. We were also limited because of the lack of buoyancy that we otherwise would have underwater.

Site Recording

Offset Survey

The offsets survey was meant to measure positions of the various components relative to a tape baseline fixed between two control points. Our offset measurements are distances at the right-angles of the part/object of interest from the baseline. Our first step was to set out a tape-measure baseline between two control points, which run through the center of the area to be recorded. Distances were measured from this baseline horizontally. Sketches, results, and details of the offset survey can be found in the gallery.

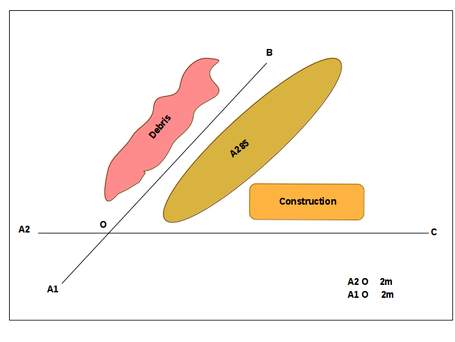

Trilateration

Another survey method we used was trilateration. Trilateration works by creating a triangle, taking two measurements from a feature to two chosen points on a baseline. It is a type of survey efficient and quick, and these are the types of surveys we could use due to time limitations during our field works. Results from trilateration on the construction portion of the shipwreck are shown in Figure. We applied the trilateration survey technique to the bronze Age boat project as well. We created a triangle, taking two measurements from a feature to two chosen points on a baseline. The recording is shown below as well as the drawing of the outline of the boat that resulted from the survey.

Photogrammetry

We also performed photogrammetry on the construction part of the mina shipwreck. Photogrammetry is also a pretty efficient survey technique. It requires photos of the object/site of interest and an online software is used to reconstruct the site. It is a very popular technique in the field of maritime archeology, as it is used to monitor site modification over time. The results of photogrammetry applied to the construction part of the shipwreck no. A285 are shown in the figure. The photos we used for this reconstruction have been taken by our instructors as we were not able to physically go to the site due to Covid-19 precautional restrictions.

Testing Hypotheses

Experimental Archaeology and the Bronze Age Boat

What is it?

Experimental archaeology is an accurate replication of the materials and methods used to recreate artifacts. This form of archaeology engages in a trial of various methods, focusing on relation to technology. The materials, technology, and methods used must be as similar as they were during the time of the artifact's construction. It is used to test theories about the history of human behavior. The Bronze Age boat site tries to recreate a boat from the Gulf using these methods. We experimented with materials such as reed bundles, stakes, tamarisk wood logs used in the boat’s frame, and rope.

Our class was asked to create a reed bundle to be tested at NYU Abu Dhabi to determine the most accurate strength level of such bundles in Bronze Age boat building. We utilized the physical boat for trilateration work.

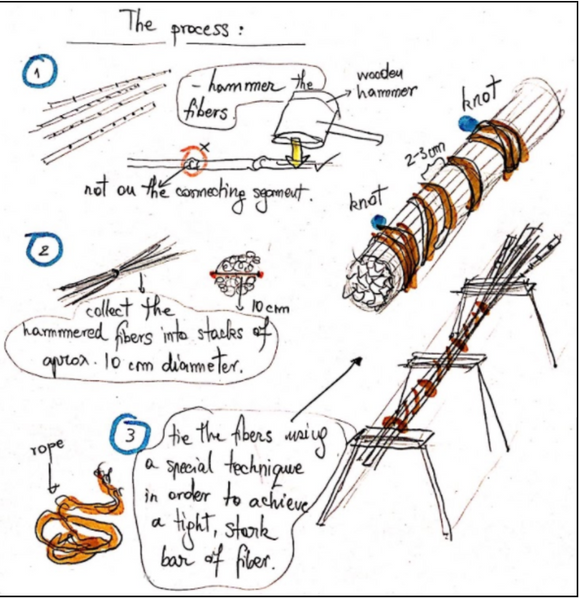

Day One

On day one, we learned the bundle construction process. First, one must crush the reed bundles, but not vertically along the joints. The results should be a flat, bendable reed. We needed enough reeds to reach a 10 cm diameter, and we measured this using calipers.

While the others crushed reeds, some worked on ropework (see photo). This is needed to tie the bundles at the end and the middle to continue the construction process. Once the bundle was tied, we began the compacting process. To do this, we had to tie a triple knot. The first person would take the rope and pull on their side. The other hammers the reed bundle to make it compact. They then alternate by passing the rope.

We worked on making the stakes to be later hammered into the bundles. To do this, we utilized a chisel and a wood block for support. The idea is to hold a piece of palm wood vertically and run the chisel parallel to the sliver of wood. You then taper the end of the stake until it is sharp and thick.

Day Two

Day two was combining the reed bundles. To do this, one must double the rope using a twisting technique to ensure the bundle strength.

Next, we tied the rope and looped it under and up through the bundles using a metal poker. One must loop the rope over and under the wooden log. Each time you loop the rope through, pull it tight, and your partner will hammer and hit the bundles together. You continue until you reach the other side, and then tie a knot two to three times over the end. This goes until the bundle has equally allocated wooden logs.

Next, we slid two palm reeds into the bundle for support. At this point, we hammered the stakes into the bundle to hold it together.

Frame Reports/Drawing

On day three, we worked on frame reports for tamarisk wood logs. Each log was used on the ship's frame. The diagram below demonstrates the frame parts.

Boat parts are measured three ways: sided, moulded, and length. The first part of the frame report entails the measurements of the frame itself. The moulded measurement is when the frame is sitting at as a U shape, or the up-and-down dimension. The sided dimension is the frame thickness.

To get the perimeter and thickness of the object all the way through, line it up against a straight edge and use a measuring tape or ruler to get the measurements.

We did a detailed drawing on the same day, refer to above.

Governance

Nautical Archaeological Society

Recognizes the non-renewable nature of cultural heritage wherever situated.

Supports all activities that further the recording, preservation and responsible management of the cultural heritage.

Respects the letter and spirit of national legislation and that of international legislation, codes of practice and charters that are designed to protect the cultural heritage.

Recognizes that best endeavors should be made to disseminate the results of research in appropriate publications and other media within a reasonable time.

Recognizes that best endeavors should be made to encourage and educate others to take an interest in nautical archaeology and to develop their experience and skills.

UNESCO

Obligation to Preserve Underwater Cultural Heritage - States Parties should preserve underwater cultural heritage and take action accordingly. The Convention encourages scientific research and public access.

In Situ Preservation as first option - The in situ preservation of underwater cultural heritage (i.e. in its original location on the seafloor) should be considered as the first option before allowing or engaging in any further activities.

No Commercial Exploitation - The 2001 Convention stipulates that underwater cultural heritage should not be commercially exploited for trade or speculation, and that it should not be irretrievably dispersed.

Training and Information Sharing - States Parties shall cooperate and exchange information, promote training in underwater archaeology and promote public awareness regarding the value and importance of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

UAE Law

Within the United Arab Emirates, “conservation, protection and capacity building activities are carried out through reinforced cooperation among the States Parties, the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies and UNESCO Offices in the field, in addition to the Arab regional Center (ARC) in Bahrain." There is also an Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture & Heritage, which was founded in 2006. In 2011 it launched a preservation project to research the cultural heritage and life of those living in the region prior to modernization in the 1960s. It also maintained a historic preservation program for historic buildings in rural areas of the country. It seems as though the conservation of sites within the UAE and more specifically Abu Dhabi is a reasonably new process. Also, until recently, there was also no mention of underwater or maritime sites. However, in January 2019, authorities, underwater and maritime archeologists from the Arab Region met for a workshop on the protection and management of the maritime, coastal and underwater cultural heritage. This hopes to have raised greater awareness of the existence of the rich cultural heritage of maritime sites, even though the UNESCO 2001 Convention on Underwater Cultural Heritage has been ratified by only 11 of the 22 Arab Member States. Whilst there are contemporary attempts to improve the conservation in this area, there has been a lack of such protection in the past, which puts the site in danger, as outlined in the Recommendations section of this report.

Research and Interpretation

The sites selected were effective as representations of two ship forms that are bookends to vessel development in the Gulf region. The Mina site provided prime examples of what might be considered a conventional ‘dhow’, while the Bronze Age Boat lab site gave us excellent insight into ancient shipbuilding techniques and the ways in which these vessels were used. Both sites would allow us to study maritime tradition in the Gulf throughout a long historical period, from pre-Christian times to the modern day post-unification UAE. One part that was particularly prominent in our site research was considering what the purposes of these vessels were. We identified one wrecked dhow in the Mina site as possibly being a floating restaurant, with signs of cooking oil/gas containers and kitchen appliances. Another vessel was identified as likely being a fishing boat, still bearing nets and a container for storing caught fish and crustaceans. This was very useful in answering our research questions on the type of dhows we had found, what their contents (and therefore their purpose) were and where their place of origin was.

The three days on site at the Bronze Age Boat lab proved to be an effective hands-on learning environment. Aside from the pain and numerous hand blisters that came with whittling down spikes, and the mild confusion about types of knots used when lashing together bundles, our group learned how to efficiently and effectively apply measuring and recording techniques such as photogrammetry and measuring individual boat components from a baseline.

Moreover, our research data was selected to focus on specific elements of maritime culture, particularly the interpretation and representation of ‘dhow culture’ through film, as well as academic essays on the topic. We analysed and discussed excerpts from the films ‘Hamad and the Pirates’ (Bahrain, 1971), ‘Between the Two Banks’ (UAE, 1997), ‘The Cruel Sea’ (Kuwait, 1972) and two more recent videos - one being an Abu Dhabi tourist reel released in 2017 called ‘Your Extraordinary Story’ and the other being an Omani film supported by the Ministry of Heritage and Culture called ‘Al Boom’ (Oman, 2006).

Conclusions

Does Dhow Culture Exist?

It is apparent that governing bodies utilize heritage, especially maritime heritage, to promote a facade that attracts tourists. There appears, then, to be a dichotomy of heritage in the Gulf. There is a romanticized dhow culture that boosts tourism and nationalism. But at the same time, there is and was an authentic maritime culture that is specific to the Gulf, but is situated in an Indian Ocean tradition. It is impossible to generalize the Gulf dhow (or more properly, maritime) culture to the Indian Ocean. It seems more proper to say that each location in the larger Indian Ocean trade network has a specific tradition around its maritime practices, and that these regions share a general history.

Mina Zayed

With all of this training we feel prepared to return to the field in the future and conduct similar surveys on all of the ships in the Mina Zayed shipyard. Mina Zayed proved most useful for work on the NAS guidelines and underwater archaeology guide. We believe that Mina Zayed was more relevant to our research on dhow culture because it provided a more tangible case study for viewing dhow culture up close in the UAE.

During our field work, we found many objects linking the ship we were assigned to with the food industry. More research could be conducted in the field to find more connections to local or international institutions. What we lacked during our field expedition was adequate time to really investigate more on where the ships came from and the time periods they were mainly used in. We recommend returning to the site and taking samples of objects around the ships, such as oil containers to conduct research on the labels and brands, as well as biological samples of barnacles that have grown on the bottom and sides of the ships.

Bronze Age Boat

From this project, we conclude that experimental archaeology has value and should be pursued more frequently and with less criticism. Experimental archaeology is a great tool for teaching archaeology and students of maritime history about the construction processes of ships. It also gave us a deeper understanding of boat-building practices and the labor that goes into crafting such a ship. Experimental archaeology should not face the criticism it does for being anti-academic, and it allows scholars to be one step closer to finding historical truth.

Limitations

Due to COVID-19, the 2020 section of Shipwrecks and Seascapes was unable to complete all of the necessary fieldwork. In many ways, this limited what we could present to the NAS as well as complicating our individual research. This caused our class to take a more art historical approach to our research, with many focusing on tangible depictions of dhow culture in popular media.

More time is necessary to conduct full out research on the ship at Mina Zayed, to determine its purpose and its role in the UAE maritime tradition. Lastly, it would be useful to follow up on the strength testing being done on our Bronze Age boat bundles.

What Next?

Our recommendations for these sites comes with a sense of urgency. The ships in Mina Zayed frequently circulate throughout the seasons and to the government’s will. This means that, over time, there is a possibility that we lose access to the ships we were working with, or the calculations we made may be tampered with due to environmental changes. Therefore, we suggest returning to the site and recording as much information as possible, as soon as possible. For example, more surveys can be conducted to record information, or more samples can be taken to do further examination in a lab or other academic settings. Additionally, we only focused on one wreck, but there are at least seven ships that still need to be surveyed, photographed, and measured. Because the UAE is strict about property and trespassing, it may be difficult to return to these sites and maintain the ships as relics. Their frequent circulation cannot be controlled, so the best path moving forward would be rapid surveys of the location.

We believe these sites are worth pursuing due to their cultural relevance. If preservation of a local maritime heritage is important for the UAE, then they should work on preserving these dhow boats and situating them in a historical context, whether that is a museum or heightened access to archaeologists conducting research. These ships do not belong in a landfill, and further research will prove that.